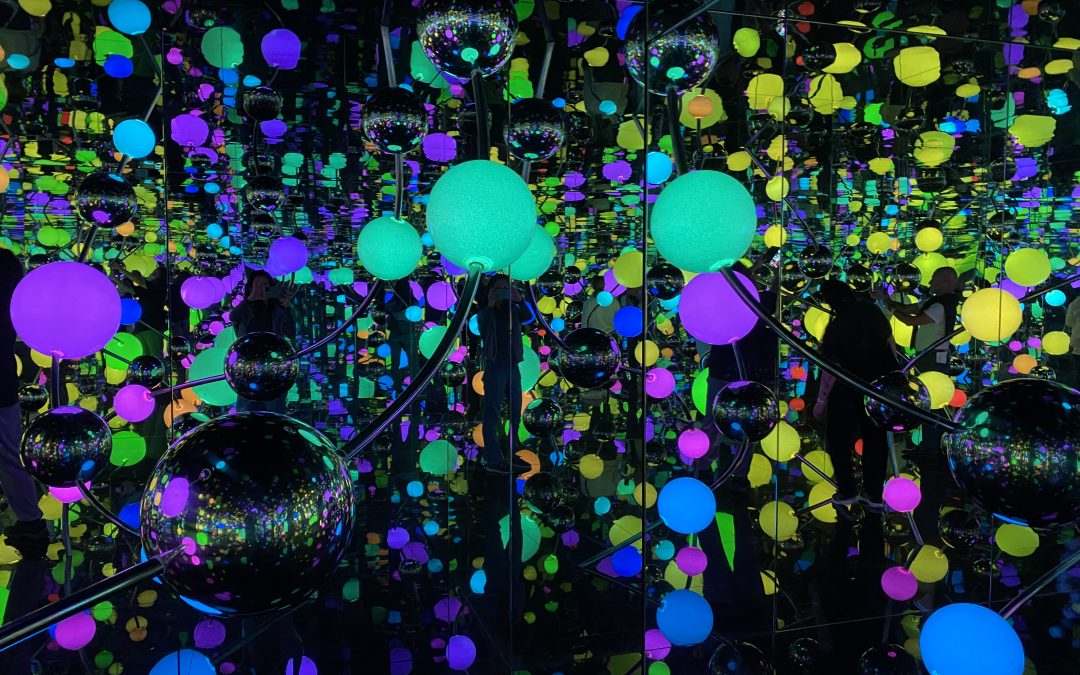

Bold, eye-popping colors; vast fields of polka dots; supersized ceramic flowers and vegetables; peep shows that hurl the viewer first into a Pachinko game, next into a Day-Glo world like that of the Teletubbies; polyptychs, composed of canvases featuring organic patterns gone wild, lining cathedral-sized walls; tiny cabinet rooms filled wall to wall, ceiling to floor with balloons resembling cotton candy or Saturday Night Fever style colored lights; a forest with towering pink polka-dotted trees as magical and enticing as that Dorothy walked through on her way to the Emerald City.

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s artwork, evoking the same giddy sense of release one might experience after consuming a hefty dose of hallucinogenic mushrooms, enables museumgoers to step straight into the Beatles’ Strawberry Fields. Watching hordes of visitors sporting enormous smiles line up to take selfies within one of the Infinity rooms or be photographed beside any number of the other installations, say a pumpkin large enough to feed a small nation, immediately evokes the carefree pleasure of Cindy Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

I’m a Kusama groupie. Back in November 2019, when the world was a different place, I finally had my first chance to view her work. It came at the steep price of undergoing freezing temperatures on an unforgivingly chilly New York City Street. I stood for four hours in a line that snaked from the David Zwirner gallery on 19th street all the way down 11th Avenue where it parallels the Chelsea Piers and moved slower than molasses, to gain the pleasure of two minutes (yes, only two!) in one of her famous Infinity rooms. I’m never going to forget that experience, neither being immersed in a gloriously magical world whose boundaries were erased by tinted lights and cleverly angled mirrors nor thinking I might die from the bitter cold, frozen solid to an unforgiving slab of concrete. The only saving grace was sharing it all, even the wretched part, with an especially wonderful friend. We treasure the photos we have documenting our folly, both those we took within the room once we’d finally gained entry and those taken on the street, bundled up in winter coats, pressed together to stave off the cold, noses as red as Rudolph’s.

It was with that same friend that I attended another of Kusama’s exhibitions, this time, ironically, in similarly extreme conditions. In early July 2021, just as the world thought it was emerging from the COVID pandemic (haha!), she and I ventured out to the New York Botanical Garden on what ended up being one of the hottest days of the summer, the temperatures hovering around 100 degrees Fahrenheit (40C) with insane humidity. We didn’t care. Freezing cold or blistering hot, nothing would deter us from making another pilgrimage. Armed with sundresses and floppy hats, we slowly made our way between the various pavilions, spread far and wide within the vast garden, ducking into the shady areas beneath the trees lining the sun-bleached paths, pretending we weren’t hotter than blazes and that our clothes weren’t soaked through with perspiration; fortified by the honor of having another opportunity to step into Kusama’s enchanted world. The fact that we drooped as much as the abundant flowers lining the trail, simply wasn’t didn’t matter.

Spread throughout both the old and new wings of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Kusama’s present retrospective compliments and expands on the wonders I experienced at those first two exhibitions. It is so fascinating and transporting, so vast, that I’m delighted to have secured tickets for several visits. Kusama, at the end of the day, is better than any narcotic.

So, what is it? What’s the big deal about those polka dots? Why are people willing to line up for hours to get into one of those 13-foot square (3-meter sq.) Infinity rooms?

I believe it’s all about the magic; that human beings fundamentally desire to be swept away by a world of make-believe, one in which there are no deadly viruses, no potential for nuclear annihilation, no random acts of violence cutting down innocent people, nor racist-driven hate crimes—a world as pristine as Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and as fantastic as that created by Willy Wonka. Who, among us, wouldn’t have given anything to get one of those Golden Tickets?

Unfortunately, while the artist arrived at those signature polka dots early on in a straightforward fashion, working with nets to filter nature through fields of round, oblong and sometimes amoebic shapes, her oeuvre was soon to turn from innocent to disturbing. Although Kusama’s world, characterized by explosively inviting formal means–super bright colors, aesthetically-pleasing lines that converge pleasing designs or congeal into that childhood favorite, illusion-inducing lights, and mirrors—is ostensibly one of pleasure and delight, its conception, as attested to by the artist’s testimonial, indicates something else entirely. Carried away by the overpowering effect of her manipulation of color and shape on the canvas, Kusama sought to extend the natural limits of the ‘framed’ canvas to include the room in which she was painting, covering the floor, the furniture, the walls, and eventually, her own body. She was attracted by the idea that she could erase herself, be swallowed up whole by the world she’d created. Her obsessive repetition of this practice, to this day, is nothing less than a means of self-obliteration. So maybe this isn’t happy art after all. Cindy Lauper has been silenced.

For the visitor, the Infinity Rooms, which in many ways are the main attraction of Kusama’s exhibitions (as attested to by long lines of patiently waiting visitors including myself), are nothing less than magical kingdoms. Once the doors are closed, we are bombarded by a bevy of changing patterns dependent upon where we stand, in which direction we look, and how we move. Mirrors on the walls and ceiling reflect boldly colored lightbulbs affixed to the various surfaces, creating a realm as rich as a honeycomb and miraculously transforming a small, claustrophobic space into one that both extends to a boundless unknown and surrounds us in an intimate embrace.

For Kusama, these masterpieces represent the artist’s horrifically sad attempt to make herself disappear but also count as safe spaces, ones to which she could retreat and finally take a needed break from whatever was happening elsewhere. In this way, they are as much of service to the visitor in these complicated times, as to the artist herself. Kusama’s artwork, the proof of her mental unraveling, offers us the perfect fix to this wretched and seemingly endless COVID era. Stepping out of a reality we cannot control, one stuck in an infinite loop of unknowns, into a hypnotic one hyped up by steroid-boosters and mood-altering psychedelic colors, a place located somewhere over the rainbow, is just what the doctor ordered. In the end, Kusama’s world is no less real than the one we’re living, and in many ways, far more appealing.